Art by Mohammed Fayaz

Like thousands of dieting/exercise books selling change instead of body acceptance, self-help gurus sell enlightenment like it could be bought for $9.99 plus tax and shipping fees.

The Love Guru (starring Mike Meyers) sums up the diversity in the self-help industry.

That is not to mention the lack of diversity. Apart from the notable example of Deepak Chopra, the majority of self-help books are written by white authors applying Buddhist principles. While some of what they say might ring true and is extremely helpful (don't get me wrong, I love Elizabeth Gilbert), the content can be appropriating, confusing, and not always relatable for me as a person of color.

So, how exactly does one start to heal?

Do we just take a month-long trip to India to find ourselves? What if we are already from around there?

Do we buy a self-help book? And if so, which one?

I started my self-healing journey a couple of years ago, after a physically violent relationship taught me that, if I did not learn to deal with my past, it was going to seep into my present and follow me wherever I went. I was one of the people Elizabeth Gilbert describes “who got tired of their own shit and decided to transform.”

Now I have been in therapy for over seven years and made tremendous progress since, but there was still work to be done. In fact, there is always work to be done.

Me tired of my own shit.

[pictured: Dre from Blackish sobbing on a couch]

With the amount of time and lack of guidelines, let alone the cultural understanding, the process of self-help can get discouraging. As a queer and trans person of color who struggled for years to understand what healing means, I've learned a few things on my self-healing journey that countless self-help books failed to tell me.

We all may have our different reasons to heal, but I believe that deep down we are all connected by the same fundamental human experiences of love, acceptance, and loss.

1. Accept where you are at.

All my life, I’ve been told that I had to reach a point of healing and self-love - that “a-ha” moment when I will be perfectly whole.

Most people seemed to have it, while I still struggled with insecurities and past hurt. I have searched everywhere in therapy, in self-help books, and even in hours of solitude, but never got answers I needed. Some days I thought I was doing better, while others I felt I was regressing, especially during stressful situations. It all took time, and I feared it would take me years to get to a point where I could say I was “healed.”

One thing, I came to realize is that we all are survivors, and healing is a lifelong process. If you are human, you have been hurt and traumatized, whether it is by your family or by everyday street harassment. Healing is a daily cleansing process, because we are healing every day from numerous microaggressions.

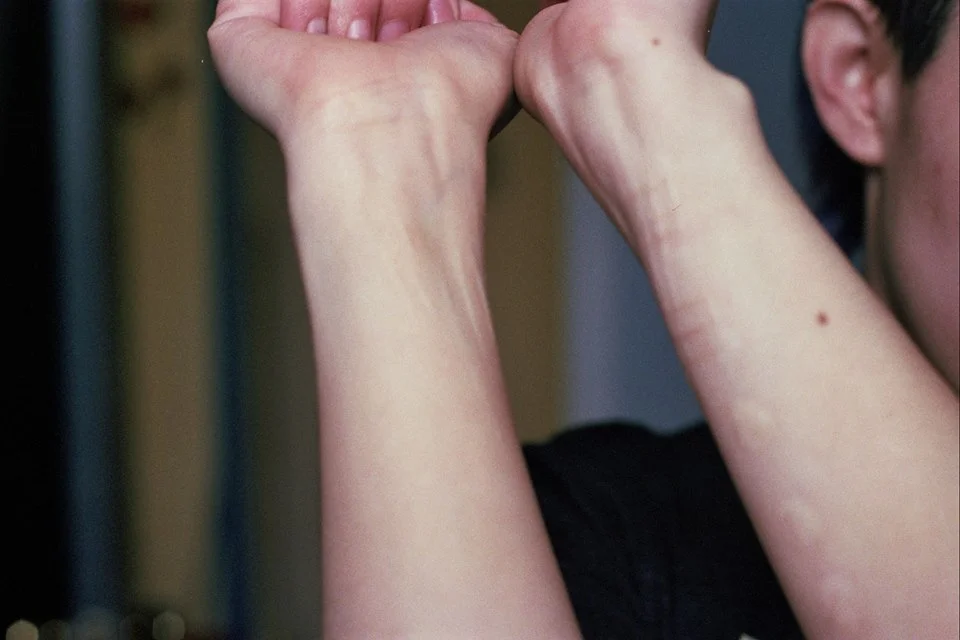

What struck a chord with me the most is a concept that trauma survivors are never broken – we are just “bent” in extreme situations.1 Like trees, we bend in extreme conditions to survive, and we do that through dissociation, coping mechanisms, self-harm, etc. Our minds and bodies just learned to adapt to deal with unnatural circumstances.

Healing is nothing but a journey to get back into the shape we were before the trauma occurred, or maybe even find an even better way to embody fullest selves. We were never broken to start with. All we are doing by healing is getting back to our most natural state of being and feeling.

2. Forget the “meditation” fads – be here now.

Meditation is probably one the most overused and appropriated buzzwords in today’s pop culture, but not without a reason. Studies have shown that training our minds to be in the present moment changes the structure of our brain and its functioning, ultimately healing it.

However, instead of countless hours spent at meditation workshops, shambhala centres, and colouring sessions, I wish someone told me that being present did not cost money, or time; it wasn't a fad that I had to keep up with.

Being present is about being here in the now – whether I’m actively listening to a friend, enjoying my meal, or just walking around the city. It simply meant taking time from my day to get out of my thoughts and notice my surroundings.

Being present is about learning to come back to our bodies, from which we learned to escape from all these years.

Most of my so called “mindfulness” now happens on the bus, while cleaning dishes, or taking a shower. I started with timing myself 5 minutes a day, giving my full undivided attention to my surroundings. I timed myself noticing the sounds and people around me or simply following my breath. I then progressed by increasing my concentration to 10, 15, to 20 minutes a day.

Nowadays, my brain is in the habit of concentrating on my breath and the present moment instead of spiraling into panic attacks. For me, this skill has decreased my intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, and insomnia.

3. Don’t fear the dark emotions.

Western media portrays happiness as the ultimate goal. Take the example of all the countless titles available on the subject: “The Happiness Project,” “Stumbling Upon Happiness,” “The How of Happiness,” and so on.

Constant happiness - the ultimate goal in life?

[Pictured: a scene from the Simpsons with two characters at the dinner table, big round smiley faces over their actual faces.]

Dark emotions like loneliness, sadness, or anger are expected to be suppressed and discarded. We’re told that expressing those dark emotions makes us look bad, needy, or different from those who act composed and put-together. Yet, those are the very emotions that protect us.

Many of us, like myself, believe that putting on an armour around feelings would protect us in case future aggressions, but that is not always the case.

According to Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk, in his book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind & Body in the Healing of Trauma, our bodies carry residual trauma, and by putting on an armour around our feelings, we are more likely to experience similar abusive situations.2 Engaging back in our bodies helps us feel pain and danger again, which in turn signals our bodies to run away from abusive situations next time they occur. Similarly, emotions also signal which people and situations are good for us.

For many years, I believed that suppression of anger or sadness would protect me from violence. Anytime I felt distressed, I went to my safe space of reading to drown out my uncomfortable sea of emotions. Not stirring the boat kept me out of harm’s way, I thought.

Recently, after witnessing a physical fight break out in front of me after many years, to my own surprise, I found myself automatically opening a book and reading the passages to myself, as a way of disconnecting. I dissociated the same way I did when I was 10.

This time, I caught myself, and made a different braver choice – to feel the pain. I closed the book, stood up, said my part, and walked away. Although I knew I could not change the situation, I suddenly felt a wave of relief take over me. For the first time, I exercised control to save myself.

Pain is a signal that something is wrong and that things need to change. The key is to discern emotions and listen to what they tell us about ourselves and the situation.

It is okay to be vulnerable, needy, or sad – those are the feelings that make us human. Those are the feelings that make us reach out for support. They are the feelings that help us find people who can hold a safer space for us. Thy help us connect to others, and that is where love is born from.

4. Redefine Love.

Loves heals all; isn’t that what the song lyrics say? However, in her book “All About Love,” bell hooks argues that the western culture fails to give a concrete definition of love, often putting an emphasis on romantic love or that “perfect” family that we missed out on our childhood as the only redemptive and healing types of love. Community or external relationships are often downplayed or ignored. Hooks defines love to be “a combination of six ingredients: care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect and trust.” While for some people, romantic and familial love embodies those aspects, for others love takes different forms.

This song is rumoured to be about domestic violence.

[Pictured: a sheep standing in a grassy field with the caption, "What is love? Baby don't herd me."]

For me that definition of love was found in my extended family members and friends who taught me that I was lovable when I felt I was not.

One evening, after I called a crisis line, my best friend told me, “I will love you whether you achieve your dreams or not, whether you decide to transition, or whether you decide to go back on all your decisions. I will love you not because of what you achieve or become, but for what you mean to me.”

In that moment I felt that all the love and acceptance I lost came back to me.

Experiencing abusive or neglectful environments, whether it is through homes, schools, or even past relationships, we begin to believe the mistreatment we experienced as “normal.” We need to rebuild communities filled with new relationships that redefine “healthy” in a way that supports individual and collective wellbeing.

Love is out there, and there any many beautiful queer people, allies, or even animals that can remind us that family is more about connecting through mutual care than through blood.

5. Read stories about people who are like you.

I learned to love myself when I saw other people loved themselves and embraced the very same flaws I rejected in myself. Something about seeing these beautiful and resilient people stand tall in their imperfections and still be “worthy” gave me the courage to do the same.

Making a list of the people who looked like me, had the same struggles, and were still admirable, made me realize that I had skewed perception of “worthiness” and it was not being a young good-looking millionaire with no problems, like most self-help books taught me to aspire to be.

We don’t always need self-help guides to learn to accept ourselves; we need to find people whose stories and struggles speak to us. Different books speak to different people.

Some stories that helped me were:

Dirty River by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. Her memoir on being a South Asian disabled femme survivor helped me reconcile my queer South Asian identity and rebuild a chosen family.

Shadows Before Dawn by Teal Swan. Teal is an abuse survivor from being trapped in a cult for 7 years. Her book gives a step by step guide to abuse recovery and self-love.

Never Broken by Jewel. Jewel’s memoir tackles topics of surviving domestic violence, homelessness, and pursuing her songwriting career. Jewel’s persistence to staying sensitive and true to herself, inspired me to embrace being open in a world that values invulnerability.

“The First Time Someone Loved Me for Who I Really am” an essay by Maria Bamford. Maria describes her struggle being a comedian with bipolar, OCD, and depression, and finding a supportive partner who accepted her journey.

6. Realize that perfect people do not exist.

It is so easy to get caught up seeing “perfect” people who appear to have little or no problems on instagram or at family gatherings. You know that cousin of yours who lost 60 pounds, works for Google, has a gorgeous wife, and two kids? Meanwhile you are single, in between jobs, and living with roommates and four pets?

We need to remember that everyone is on their own journey – doing what is authentic to them. And authenticity matters a lot more for our well-being than public image.

My journey taught me to be compassionate to other people’s imperfections and to believe in people’s potential. Having a life that violates society’s ideals has allowed me to take risks outside of what is expected of me and be myself unapologetically.

The moment we let go of what society defined as perfect, we are finally free to step outside of those lines and create something new.

It is okay not to be like other people, to have our own challenges. There is a whole world out there waiting to be connected to – waiting for us to learn to accept ourselves just the way we are, so they in turn can accept their unique and struggling selves too.

* * *

Now, I am not a therapist or an expert. I have not found myself or healed completely. I don’t even know what those words mean exactly.

I do, however, give room for myself to always be learning and working on myself, and that is what I think true self-acceptance means – to give room for failure, to forgive ourselves, and to be a work in progress. I think that is what being human is, to have the opportunity to heal every time we get cut.

Notes:

hooks, bell, All About Love : New Visions. New York :William Morrow, 2000.

Jewel. Never broken: songs are only half the story. New York: Blue Rider Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2016.

Van der Kolk, Bessel A. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking, 2014.

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

Image description:

A couple of QTPoC are on a bed together. A Black person with short textured hair lays on their stomach, reading a book. They are wearing round wire-framed glasses. A brown person is sitting on top of them, legs on either side, typing on a laptop that rests on their partner's back. They are both in their underwear. The wall behind them is brick with a large window, showing snow falling outside.

About Mohammed Fayaz:

Mohammed Fayaz is an illustrator and one of the organizers of Papi Juice. Born and raised in New York City, Mohammed's illustrations are intent on documenting his community of queer and trans people of color. With work that spans digital and mixed media, his illustrations lend a eye into a world traditionally left out of mainstream media.

About Robbie Ahmed:

Robbie Ahmed is a 25 year old South Asian transman who grew up in Russia, Saudi Arabia, Bangladesh, and now Canada. He writes about his journey in discovering what home, happiness, and healing means in context of diasporic identity. His previous work was in running support programs for queer people of colour reconcile queerness and cultural identity in Toronto, and advocating for culturally appropriate mental health services.

![Me tired of my own shit.[pictured: Dre from Blackish sobbing on a couch]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/582d23d3d1758e1a79e92999/1516907453381-PY5ZZAC3PI0E2ON51D19/dre+blackish+crying.gif)

![Constant happiness - the ultimate goal in life?[Pictured: a scene from the Simpsons with two characters at the dinner table, big round smiley faces over their actual faces.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/582d23d3d1758e1a79e92999/1516908579778-7QAWWSKZ1EU5YKKOPF5O/simpsons+smiley+face+dinner.jpg)

![This song is rumoured to be about domestic violence.[Pictured: a sheep standing in a grassy field with the caption, "What is love? Baby don't herd me."]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/582d23d3d1758e1a79e92999/1516909245091-27NCE2BV60AASV6VKV33/baby+dont+herd+me.jpg)

Lighting candles, burning sage, going to therapy, accessing medication, praying, giving offerings to the ancestors have all been ways that I heal at the intersections of my beautifully complex existence.