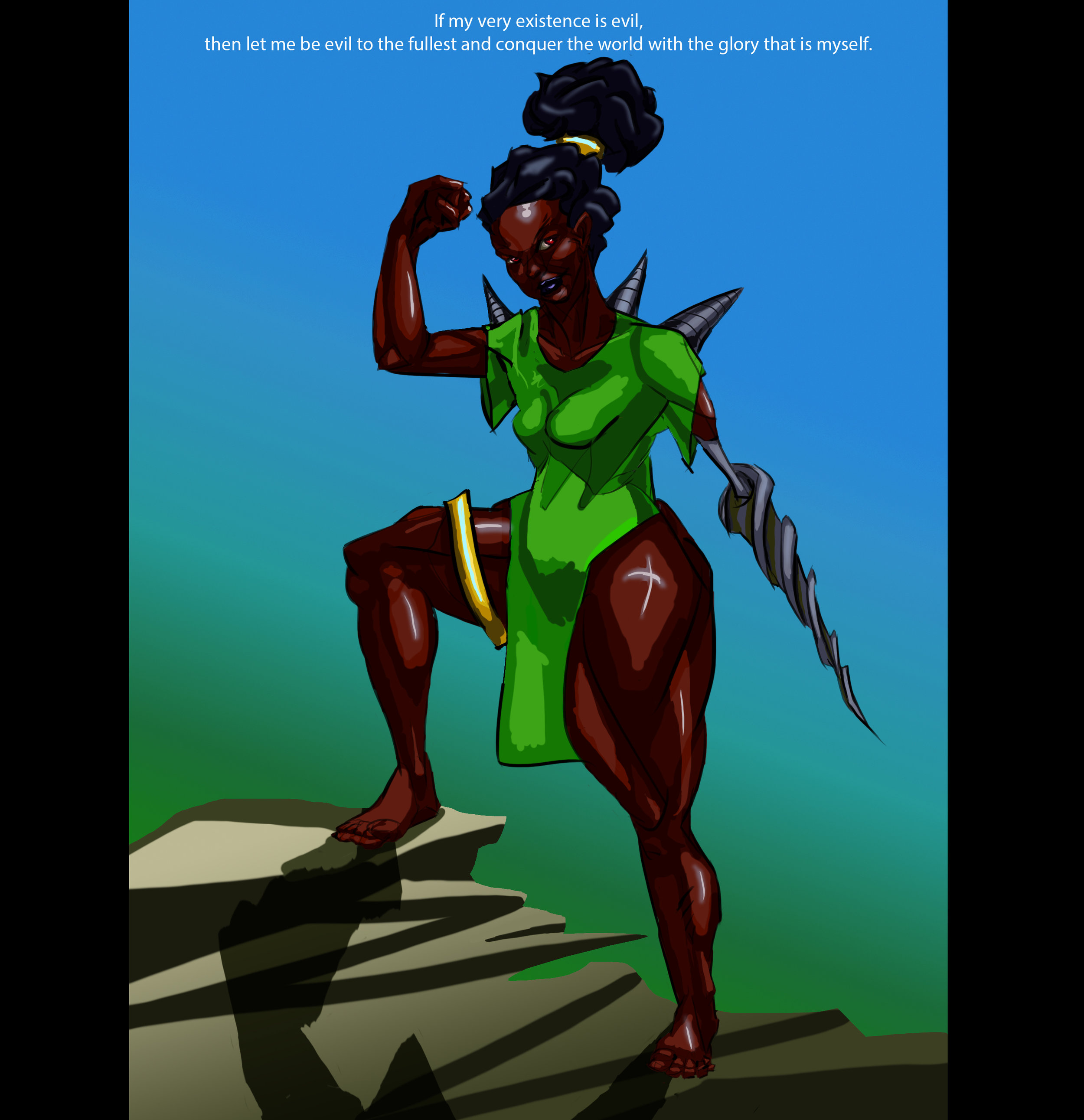

Photo by Deveney White

The white-centricism of mental health is evident in self-help books, memoirs, YouTube videos, and peer support groups. This makes friends, family, and mental health professionals less likely to see that we are struggling. On top of that, we do not get mirroring of our symptoms – in other words, we don’t see people like us suffering in similar ways – and are left to doubt our experiences and the severity of our mental health issues.

If this wasn’t the case, we wouldn’t need The People of Color and Mental Illness Photo Project, which collects portraits of POC holding up signs that say they have depression, anxiety, PTSD, and more. Dior Vargas who’s the brains behind the project also wrote an article: “People of Color Have Mental Illness, Too.”

This is where we’re at: the first stages of even seeing ourselves and other people of color within the mental health system.

Not only does this glaring absence make it harder for us to believe our experiences, but it means others are likely to deny our experiences too. If the image of eating disorders is a thin blond woman, then fat Black persons of all genders are less likely to have an eating disorder seen or validated. And without that basic recognition of a struggle that the individual can’t handle alone, there’s no way to get support from other people to heal and live with less anxiety.

This also impacts us when we do identify our depression, anxiety, and/or trauma. Going to seek help, either peer support or therapy, often means asking white people to carry some of a burden they literally can’t bear or fully understand. And if we bring up the impact of racism on our mental health, it can invite white fragility and gaslighting. So we try to shrink ourselves to fit the shared (white-centric) understanding of ADHD or borderline personality disorder or general anxiety.

There are so many ways people of color are negatively impacted by being invisible within mental health. And regardless of the specific details, the impact can make our mental health even worse. This won’t change until we’re invited to the conversation, invited without caveats about what we should or shouldn’t say.

1) There’s no end to our trauma.

Within minutes of opening The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Sourcebook, I found this: “Healing occurs in a climate of safety and pacing. When you were traumatized, you were not safe. This time, however, you will always remain safe and in control.” In other words, we just have to realize we’re safe now, and then the trauma responses can slow down.

We’re supposed to accept that trauma is in the past. But what if it’s not?

When trauma is tied to systemic oppression such as racism, leaving it in the past can be and often is impossible. Given that safe spaces are an ideal, not a reality for most of us, these kinds of statements are invalidating. If feeling safe is a required condition for healing, that makes any kind of recovery inaccessible to those of us enduring chronic trauma from the world around us.

The white picture of therapy is you sit there and talk for 45 mins about one thing that happened in the past.

But I literally can't do that.

My therapist regularly stops me to say I’ve brought up a lot already – family, work, queerness, abuse history, mania, avoidance anxiety – and need to prioritize what can be covered in this session. What I most often find myself doing is spend that time discussing present-day problems with random tangents about the past. There’s just too much happening now and too much interconnected trauma to spend a full 45 minutes focusing on any one thing that’s impacting my mental health.

That’s not to say there’s no space to heal in my life, but that the conditions of my healing involve not having access to safety or stability. And that’s ok because there are always opportunities to heal – even if the field of psychology says otherwise. Just we need a lot more opportunities, especially ones that work for POC.

2) POC healing practices and spirituality are often culturally appropriated, meaning that they can be as harmful to us as they are helpful.

So much new age “culture” steals from POC beliefs and traditions. Herbalism, crystals, meditation, the list goes on and on. Cultural appropriation isolates many people of color, especially in white-dominated locations, from the healing practices that make up the fabric of our and our ancestors’ lives – and our survival. If we see our culture being tokenized and otherwise disrespected, how are we going to have a supportive experience in the room?

Cultural appropriation pushes out the very people who are culturally bound to these healing practices, preventing them from accessing the healing they need.

When I talk about my experiences as a South Asian in yoga studios, people often react as though I’m making a big deal out of nothing, like I’m taking it too seriously or that I don’t want others to benefit from the undoubtable healing properties of yoga. Yet, the yoga industrial complex has traumatized me. As a result, it made me believe that there was no space for me to heal in this world. I spent a couple years avoiding yoga because it made me cry. But through that I’ve learned that’s the experience I need to honor myself. I need to give space to overwhelming emotions, as well as the memories of racism and repeated abandonment.

Now that I accept that reality rather than strive for Western yoga Lululemon ideals, I am slowly returning to asana practice at home. But I can’t always handle that level of physical and emotional engagement. The same goes for meditation. It should be challenging – we don’t live in a world where we are quietly with ourselves very often.

Living under the myth that healing is relaxing, easygoing, and inherently joyful is limiting for me. But that is too often the practice that’s available in Western studios and sanghas.

3) The cultural contexts of mental health experiences have been stripped away by colonialism.

There could (and should) be multiple articles on this topic alone. I’m not an expert in this by any means, but thankfully there are mental health professionals and community healers raising awareness about the cultural knowledge that has nearly been lost. For example, the book Mental Health, Race, and Culture by Suman Fernando is a great resource on this. It talks about how what we call psychosis in Western society can have more positive connotations in parts of Africa and Asia. Yet the Western mental health system uses it to further other people of color.

When our experiences and identities are erased from history, from our lineages, from our traditional systems of community – which also happens with trans identities – we can only see ourselves through the negative lenses that remain. We exist in colonized frameworks where we’re a burden, a problem, a mistake, even if there was once a community role or place of belonging for us.

We’re often isolated as mentally ill people of color, silenced from speaking our truths, and stripped of a sense of belonging. Then we are expected to get well, nobody asks if the picture of wellness that’s supposed to be the end goal is even good for us.

As Kai Cheng Thom writes in the DSM: Asian-American Edition:

“The World Health Org suggests that mental health is largely about ‘realizing potential,’ ‘working productively,’ and ‘making a contribution.’ Rather conspicuously missing, of course, is any reference to feeling good about oneself, enjoying or finding meaning in what one does, or having better (less conflicted, more connected) relationships with others […] Is that all that mental health – vaunted, elusive, so highly prized – boils down to? Do this, do that, feel this, feel that, in the right place, at the right time?”

Cultural context for our identities and experiences can help us reclaim our sense of belonging. It can free us from the social constraints of false (colonized) expectations that actually fuck up our mental health. These expectations do nothing but limit our capacity for self-compassion and break trust within our communities.

Even though they’re not perfect, the healing methods and frameworks that were overwritten to leave us with these false expectations are often a better starting point than the many of the health care systems that we have – the “care” systems that reduce access, come at a high cost, and can leave us feeling like we’ll never be able to have what we need to heal.

* * *

The mental health care system is not only different for people of color to navigate, but it also leaves out some of our communities’ most effective resources. Not everyone who’s a licensed mental health professional has the knowledge that people of color need to heal. And not everyone who’s a healer or who helps others survive is trained within some kind of certificate program.

Western psychology isn’t an authority; it has to exist alongside other psychologies in order to serve every individual’s best interest and truly support our wellbeing.

Enjoyed this article? Read: "3 More Ways Mental Health is Different for People of Color" now.

Edited by O.A.O.

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

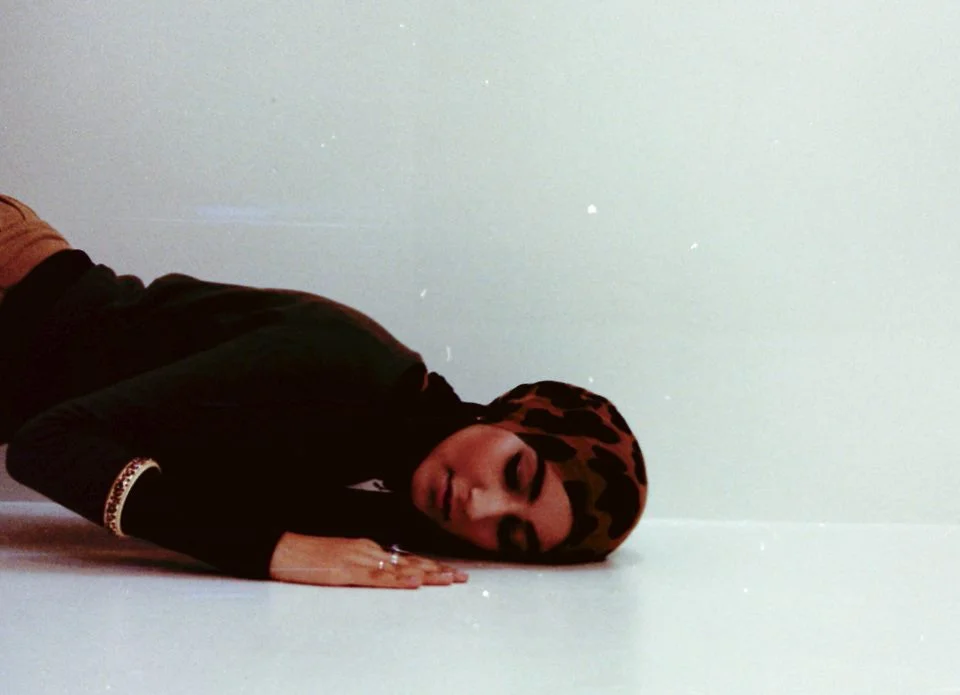

Image description:

Two books are pictured on a concrete stoop, with multicolor crystals on one side and a tall rainbow candle that bears the name of the Orisha Oya. The top book is titled "A Book of Prayer." The other book is about borderline personality disorder, claiming to be "a comprehensive & accessible guide." A Black foot appears in the top-left corner.

About Deveney White:

Atlanta-based agender/queer photographer who specializes in natural, ephemeral, timeless moments. Lover of the cornflower blue crayon, 90s culture, Lisa Frank, and social justice/human rights. They daydream frequently and play the ukulele. Follow @deveneywhite on Instagram.

About Dom Chatterjee:

The editor-in-chief of Rest for Resistance and founder of QTPoC Mental Health, Dom believes in the power of community to combat oppression. Dom is a non-binary desi-dutch-american person living with multiple disabilities.