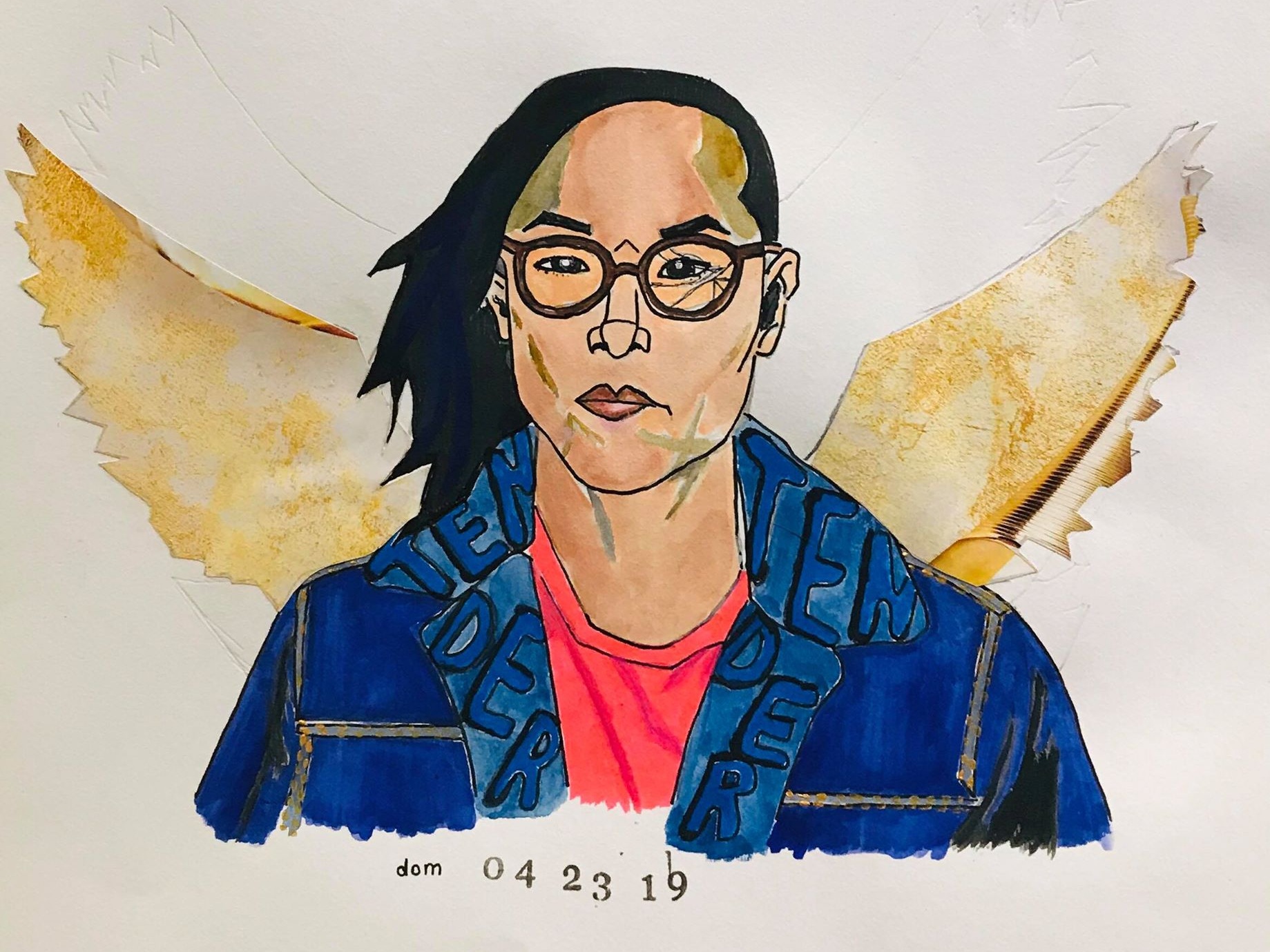

Art by Kalneria

The first time I went to therapy, I was twelve years old. I think my mom decided I was depressed, but I don’t really remember. What I do remember is spending several painfully-long sessions in in a cramped room with beige walls, across from an older white woman who asked all the wrong questions. And I remember not getting any better.

CN: trauma

By my twenty-fifth birthday, I’d survived physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; dealt with police harassment and gun violence; navigated two separate immigration processes; gone to bed hungry for weeks in a row; and faced nights where I was unsure where I would sleep. Along the way, I developed severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. I barely graduated high school, dropped out of college more times that I can remember, quit jobs I needed, and cut supportive friends and chosen family out of my life. Whenever things started to spiral out of control, I ended up in therapy. Again, and again, and again.

I never wanted to become a therapist, but in fall of last year, I enrolled in school to do just that. I promise you, this wasn’t my plan. What I did want was the chance to be a part of building something different and better than the mental health system we’ve already got. For me, that meant learning about all the worst the parts of our current mental health system, about how trauma affects oppressed people, and about every possible approach to anti-oppressive mental health care. So, I enrolled in a clinical social work program.

After two semesters in grad school and a lifetime spent searching out my own treatment, I’m sharing what I’ve learned about how to get what you need from a violent mental health system. I know the real solution is much more complicated, but for now, I hope this helps.

1. Your therapist’s education says a lot about how they practice.

“Therapist” isn’t a degree or field of study – it’s a job title. Therapists can have degrees in social work, counseling, psychology, or art therapy, to name a few. I decided to study social work because of the profession’s emphasis on social justice, and because I know I want to do work that extends beyond a clinical setting.

A social worker is also most likely, of all mental health providers, to help you navigate complicated systems, support you in accessing survival resources, and advocate on your behalf – so we’re handy if you want someone who’ll leave the office and help you with external factors that impact your health and well-being.

Psychologists tend to have more in-depth education about the science of the brain, but aren’t required to think as hard about privilege and oppression.

And psychiatrists are medical doctors, who often don’t provide psychotherapy at all. They’re the ones to see if you’re looking for medication beyond what your primary care provider is able to prescribe, but if you want therapy as well, you’ll generally need a second practitioner.

If you’re not sure about a provider’s background, you can ask directly, or check out their codes of ethics. If you have really specific goals for therapy, it might help to think about which field is best designed to meet your needs.

2. There are hundreds of approaches to therapy.

Oftentimes, therapists have their own ideas about which type of therapy is best. Because of this, they tend to have “go-to” approaches, which make the people they serve feel like it’s not our place to ask for something different. This needs to change.

No two people’s experiences, identities, needs, or goals are the same – and different approaches are better-suited to each of us. A good resource for understanding different therapeutic approaches is NREPP. It’s a database with information about hundreds of different approaches to therapy, including how they work, and whether they’re scientifically supported. It’s a good place to go if you’re not sure what kind of therapy will work for you. Remember: you have the right to request the modality you want.

3. Functioning labels are oppressive, but they matter. A lot.

A functioning label is an oppressive tool used by mental health gatekeepers to assess how well you navigate capitalism while dealing with a mental health struggle. Does your depression keep you from holding down a job? Did you drop out of school because of OCD? These labels empower your therapist to determine which parts of your life are problems, and to what extent, even if you disagree.

Are you a sex worker? Do you smoke pot? Did you run away from home? If so, chances are you’ll be assigned a lower functioning label. It’s disgusting. It’s also the way you get services, if you rely on community mental health (CMH) – the publically funded system of care available in the United States.

Functioning labels exist so providers can compare people’s experiences with mental health, and decide whose care should take priority within an overtaxed, underfunded bureaucracy. With this in mind, if you’re accessing CMH services, think carefully about how you want to represent your concerns before any intake assessments. Sharing in-depth information about how mental health struggles impact your life could cause providers to pathologize you in ways that impact your treatment plan. On the other hand, avoiding these topics altogether could make you ineligible for services. To study up functioning labels, and the assessments used to create them, spend some time searching CAFAS and LOCUS.

4. Your therapist might be an intern.

Nonprofits, in particular, are known for relying on intern therapists, because of funding limitations. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Most interns know they aren’t experts, and are more willing to learn. They’ve also had less time to get burnt out, and are genuinely excited to work with you.

On the downside, interns are temporary. I once had an amazing intern therapist tell me abruptly after our third session that she would be ending her placement at the end of the day. If your therapist is an intern, ask them directly what their schedule is, whether they have any upcoming semester breaks, and how long they’ll be in their position.

5. A good therapist has more to offer than coping skills.

For most of my life, therapy has been a series of hour-long conversations about all the things I should do to cope with my depression, anxiety, flashbacks, and hallucinations. I was given laundry lists of things to do when I couldn’t get out of bed, when I had no appetite, when the voices in my head wouldn’t go away.

Don’t get me wrong: these skills are necessary. Healing takes time, and between now and then, we have to find a way to get to the grocery store. But coping is a bandaid over a deep wound. It’s also a major source of disparity in mental healthcare between poor people and people who are middle class or wealthy. Since most low-income folks in the United States rely on free or sliding scale services for mental healthcare, our providers often want us in and out as quickly as possible. After all, we’re not profitable to care for – and in this country, that means we’re less of a priority.

Coping skills are strategies we use to cover up the symptoms of mental illness, while true mental health treatment digs deep, and addresses these issues directly. When people have the money to pay for their care, therapists are usually much happier to invest months or years in a more thorough healing process. The result is that poor people often get lower quality mental healthcare than clients with more money.

If you rely on free or sliding-scale services, and feel worried your therapist is stuck on offering coping skills, you should know you have a right to push back. Ask them what they can offer you besides coping skills, and remember that you’re worth it.

* * *

Accessing mental health care is almost always hard. For queer and trans people of color, it can sometimes feel impossible. These tips won’t transform an oppressive industry, but I hope they’ll help you feel more confident, armed with tools to help you navigate it.

Editor's Note: Look to National Queer & Trans Therapists of Color Network (NQTCCN) for an ever-growing directory of mental health professionals in the U.S. who can address intersectional concerns.

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

About Kalneria:

Kalneria is a queer, Black artist and activist from Detroit, Michigan. She is passionate about working for social justice in her community, and is one of the organizers of Detroit REPRESENT!, a QTPOC youth media collective. She loves exploring different forms of creative expression, including singing, dancing, writing and visual arts.

About Lance Hicks:

Lance is a biracial trans organizer from Detroit, who has participated in and supported queer and trans youth organizing since high school. After navigating his own trauma and witnessing that of the youth in his chosen family, Lance enrolled in a clinical social work program in Fall of 2016. His vision is a world in which each of us has the tools and support we need to heal and to realize our own power.