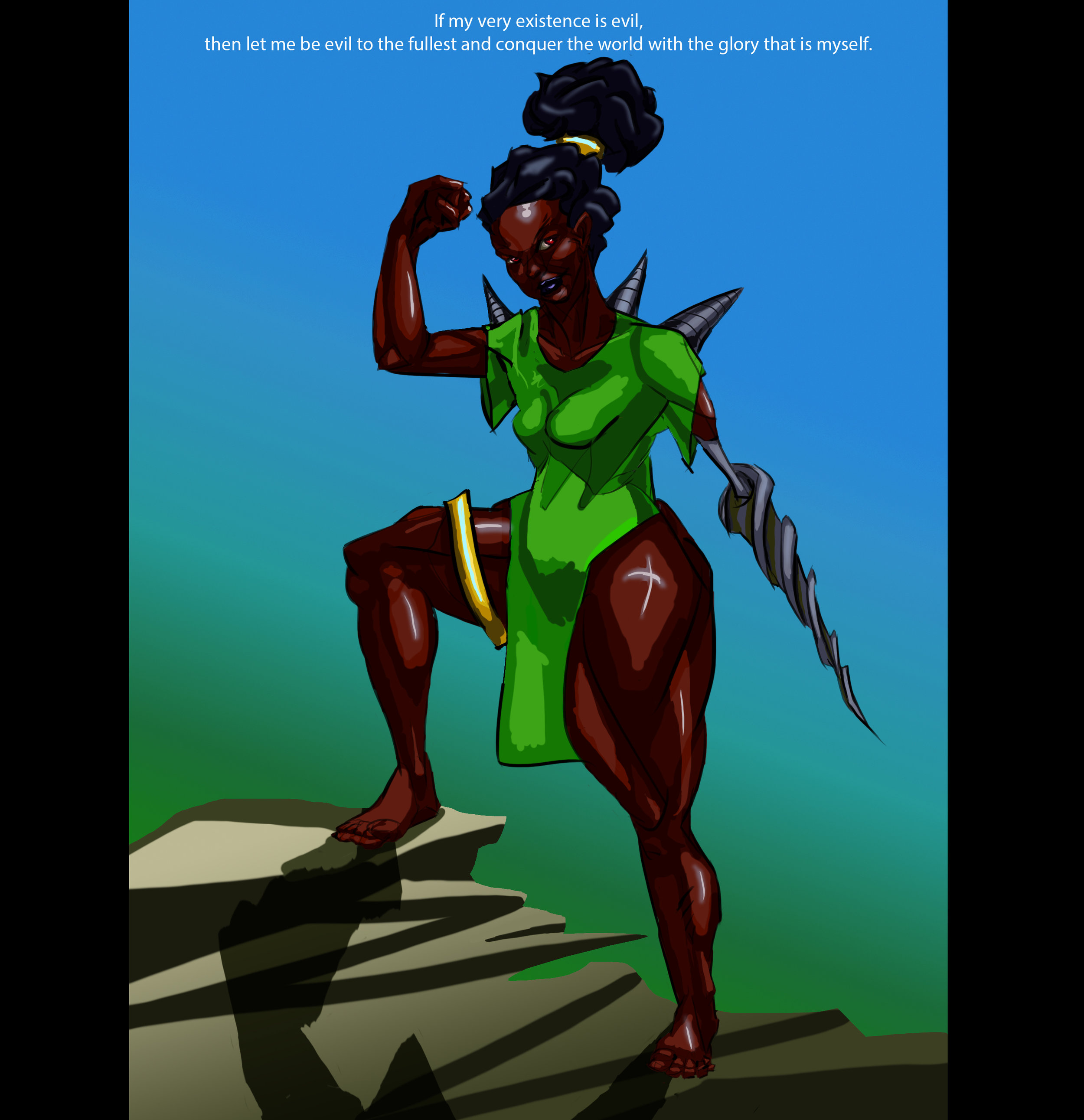

Art by Wild Iris

As people of color, we talk about internalized oppression: how we store messages against our identities and replay them, acting as our own (and others') oppressor in the oppressors’ absence. We use decolonization as a means of unearthing, exposing, and ultimately ending its impact piece by piece. In the same way, we can internalize interpersonal abuse and continue to abuse ourselves.

When we turn abuse tactics inward on ourselves, it’s not as though we’re intentionally harming ourselves. Instead, somewhere along the way, we thought these are things we had to do to survive. This internalized process of repeating the past puts us in the position of abuser or enabler or both. No wonder it’s hard to recognize and untangle this stuff! When we’re used to these patterns of abuse either from family, society, or both, these dynamics and the behaviors that go along with them can easily become the norm. If you feel like abuse is all you know, you are far from alone.

But acting like our abusers, either toward ourselves or others, isn’t going to help us heal those wounds. Even though moving into unknown territory can be scary, staying with what we know and find familiar can be more dangerous. While we want to create change in our lives and the world around us by holding our abusers and oppressors accountable, the truth is that one of the most powerful paths to becoming more accountable in society is to be more accountable with ourselves. In “The Secret Joy of Accountability: Self-accountability as a building block for change,” Shannon Perez-Darby writes:

“I define (self) accountability as a process of taking responsibility for your choices and the consequences of those choices. I deeply believe that the skill of self-accountability is one of the fundamental principles we’ve overlooked in developing community accountability models. In a process of self-accountability, this reconciliation isn’t dependent on another person’s involvement, but instead engages with our own sense of values and what is important to us. In the work of self-accountability, we are constantly striving to align our actions and our values, knowing it’s likely they will never be exactly the same. When there’s a gap in that alignment we can reflect on what choices we would need to make in the future so our actions are more in line with who we want to be.”

If we can’t work toward not abusing ourselves, we’re more likely to abuse or manipulate others to get the support we need when we’re emotionally overwhelmed. If we can’t be accountable when we replay negative messages like “I’m worthless,” we aren’t fully able to undergo accountability when we harm others: “I’m worthless, so how can anything I say hurt anyone?” None of us have fully developed the skill of accountability. So how can we change our relationship with ourselves as a means to build our capacity for accountability?

Reach for New Language

Verbal abuse is too often ignored, in part because it can sound well-meaning. Yelling isn't always abuse, and "nice" words aren't always nice. Verbal abuse is about the content and delivery of the words: insults, derogatory remarks, wishing violence on someone, backhanded compliments, passive-aggressive statements, the list goes on.

We don’t all define words the same way or interpret every phrase identically. But we can feel the intent behind someone’s words, whether they’re belittling us, minimizing our feelings, or poking around for an intense emotional reaction. That might not be the conscious intention of the person in that moment, but it’s the impact they leave. We often can’t explain why we feel what we feel as the conversation unfolds. But if words stir up something negative, that’s valid.

Unfortunately words can be sticky, and the impact of abusive language is made clearer when we use it against ourselves in our inner monologue. Insults and silencing phrases work their way into our thoughts. If someone calls a person an ableist slur or a failure enough times, then they can internalize it, associating that word with anytime they feel confused, overwhelmed, or scared.

When I’m facing the fallout of a mistake, I’m greeted by my own internalized abuse (shoutout to my parents). I can go from generally confident to saying I’m a complete failure. The feeling might be real when it shows up in those tough moments, but I don’t need to make it worse by repeating verbal abuse that I’ve received from others. Instead I can quiet that self-criticism and remind myself we all make mistakes.

We can’t change our language or thoughts overnight, but that’s exactly why self-accountability here is so important. The words we reach to in a moment of stress impact ourselves and others, so it’s important that we shift them in a kinder direction over time. The words I choose when I am frustrated with myself are the same words I might choose while frustrated with others. This kind of verbal abuse is a way we enforce impossible standards on ourselves and those around us. Free up the judgment we aim inward, and we’ll judge others less too.

Recognize Our True Limits

Abusers rely on isolating people and making it feel as though they have little to no choice but to go along with what the abusers want. When we live or have lived under those conditions, that smaller, twisted world becomes the only world we know.

Think of it like Stockholm Syndrome. Everything outside the abusive environment is so distant that it becomes scary. In response, the person held captive feels “love” for the captor and treats their prison like a home. The isolation doesn’t have to be that extreme for us to develop attachment to things associated with our abuse – and as a result avoid challenging the smallness that was falsely imposed on us. The limits of the abuser, once we leave the abusive environment, can still be ingrained in us as self-imposed limitations.

That’s not “self” like to blame ourselves, but to point to our agency to end internalized abuse. Once an outside force isn’t limiting our options, there’s only one person left to hold accountable for continuing to operate as if we’re still in that environment. And that’s ourselves. Of course, not all of these limitations can be overcome. For example, if going to a specific place causes panic attacks, it may not be a self-imposed limitation. Anxiety is often a complex situation with a lot of factors that aren’t easily resolved.

Yet even when it feels like my whole life will give me panic attacks, I have agency to explore why those limits are there, challenge myself in the ways that feel accessible, and open up in some areas from which I’ve been closed off. The journal I’m writing in is a good example. While I can’t change the way publishing treats disabled queer trans people of color, I can choose to give myself space to write anyway.

Last summer I got this journal (which says, “the best way to get something done is to begin”) just to write essays with no intent to publish. If I hadn’t done that, Rest for Resistance wouldn’t even exist. Getting a journal to grow my writing practice, without considering how that relates to the limits I feel in my publishing career, allowed me to eventually expand my options – even while they’re still very limited.

Break Free from Denial

The ways we survive can harm us – and harm those around us. It’s a hard truth to face, in part because it’s so complex. When abusers deny us our reality, it’s gaslighting. When we enact that denial on ourselves, it’s equal parts survival skill and self-harm.

Excavating ourselves out of denial, out of realities constructed of lies meant to harm us, is no small task. It requires grieving, letting go, and a whole lot more that I still hope to learn. Yet the challenge is worthwhile as this is necessary work for all of us who hope for a more supportive society. Once we start the process of undoing the hold gaslighting has on us, the work of self-accountability for our own healing process can begin.

I have repressed a lot of trauma. When awareness of my reality crept in, the shock was violent. Naming that truth spurred a year-long breakdown, which ultimately became a necessary breakthrough. I couldn’t keep living under the weight of that denial. I was on that path originally because something in me said that avoiding the full truth (which for me involved going back in the closet) would be safer. Safety is contextual, not absolute. Each person knows safety in relation to the least amount of safety we’ve ever felt. And those levels of “more safety” we rise to have an expiration date and quickly become not enough to continue forward. So I didn’t have a choice but to move through that first very heavy layer of denial and start developing a new survival skill: honoring my truth.

I’m often afraid of falling back into the gaslight-formed realities of my past. But that fear comes from understanding how easy it is to get manipulated again, that the familiar, while knowingly harmful, can feel soothing and alluring. Nobody else can stop me from entering an abusive relationship, being codependent, or trying to play the model minority game (aka seeking false hope for equality by throwing everyone under the bus including myself). Those choices are on me, and even when I have little to rely on, I don’t need to solely rely on people or realities that harm me.

We live in an abusive society, and so realistically we’re never fully free from gaslighting, especially as marginalized people, but we do have the agency to name it and other forms of abuse. Sometimes we only have agency to name it in our thoughts, but that’s no small thing. Our thoughts are the most necessary battleground to recover. Holding ourselves accountable for denial is a series of tiny choices we make in our thoughts every day.

* * *

Taking accountability for our past choices is the freedom to make new ones. Once we can see where we’re contributing to feelings that weigh us down, it becomes possible to redirect and carry a little less stress. Simply not suffering isn’t an option on the table, but the choices we do have agency to make can help us suffer a little less.

Learning to recognize how we treat ourselves badly isn’t the end goal, but the process itself. It’s an ongoing commitment to love ourselves and others more fully, to spot harm as it’s happening, and to cultivate sustainability in our lives and communities. There’s no way to know exactly what good we’ll get out of self-accountability until we start.

Edited by OAO

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

Image description:

The words, "I'm not supposed to feel ... this way," are at the top and bottom. Two bodies are drawn in the middle, abstract people in vivid blue and pink. The background behind them is yellow and blue. The pink body on the right side breaks off into pieces, which look like yellow plastic parts to a bigger whole. The blue figure has extra eyes, not on the face but in the space in front. Two hands appear at the bottom.

About Wild Iris:

Wild Iris is a writer and artist based in the UK.

About Dom Chatterjee:

The editor-in-chief of Rest for Resistance and founder of QTPoC Mental Health, Dom believes in the power of community to combat oppression. They are a non-binary desi-dutch-american person living with multiple disabilities.