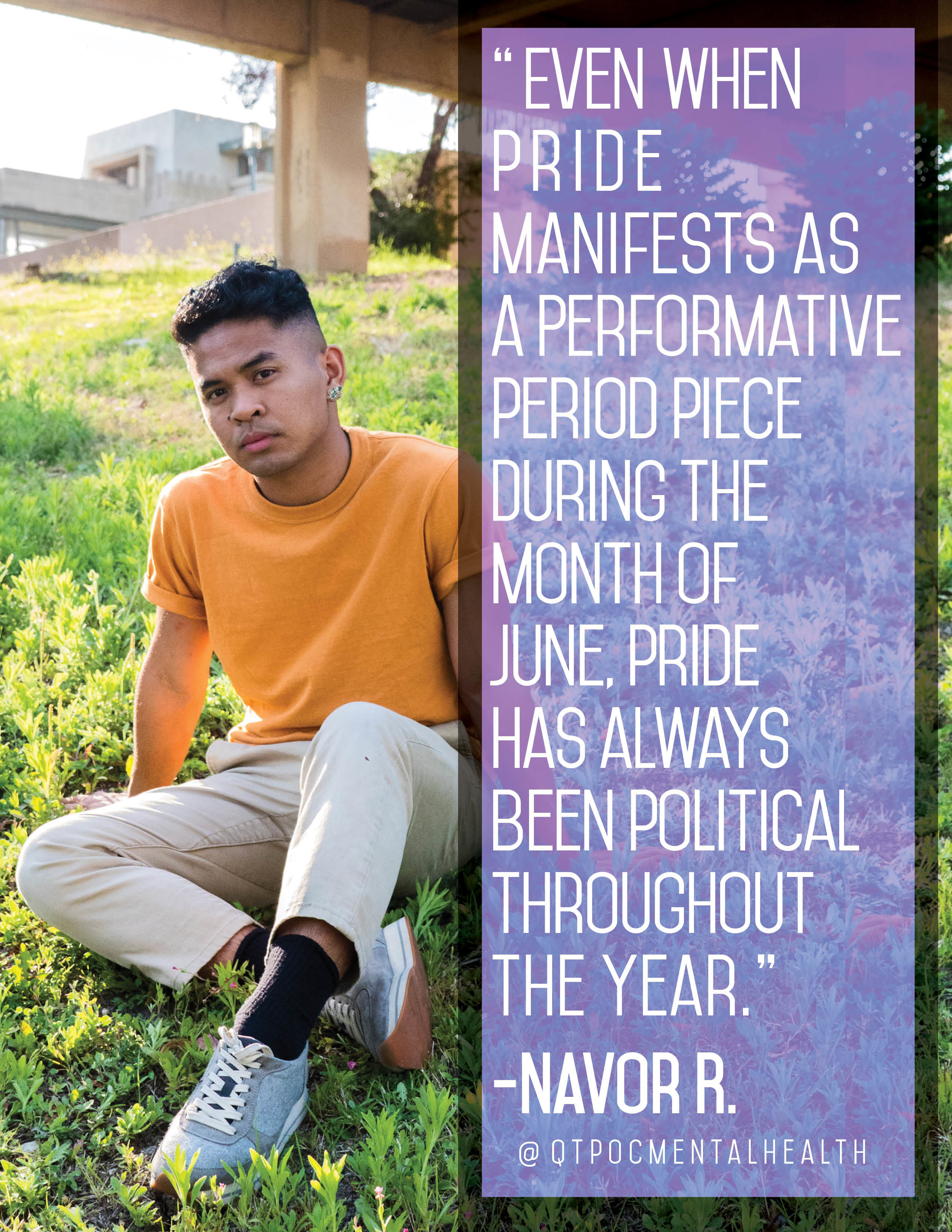

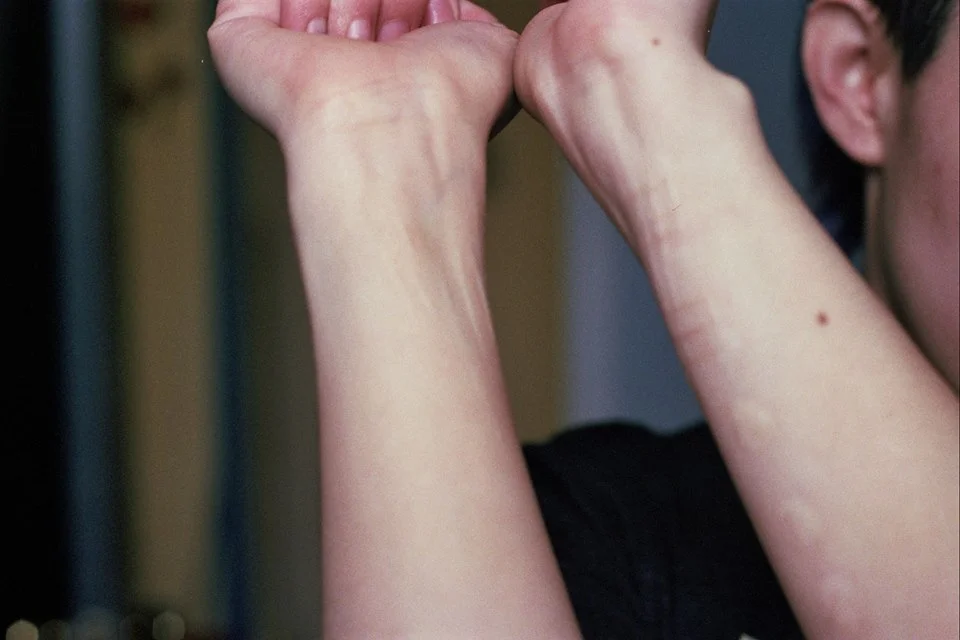

Photo by Eli Sleepless

[CN: suicidal thoughts, self-harm]

I was twelve the first time I tried to kill myself. Since then, I’ve survived multiple attempts, and years of suicidal ideation. As a mixed-race trans person, I know just how impossible it feels for my people to find life-saving support when we need it most.

When I was growing up, my chosen family of QTPOC youth helped keep me alive when therapists, hospitals, and crisis hotlines couldn’t. For too many of us, that wasn’t enough.

Mental healthcare is a vital, often life-saving tool – one to which we all deserve access. Unfortunately, like most resources that exist under capitalism, it’s heavily regulated and legislated to a dangerous degree. The result is the mental health industrial complex: a vicious system linking policy and the economy to our health.

As queer and trans people of color (QTPOC), the mental health industrial complex has always been our enemy – especially when we’re at our most vulnerable. It’s the reason crisis hotlines can send cops to our doors. The reason therapists rush us off to hospitals, instead of taking the time to talk. The reason immigration applications ask us to disclose any history of serious mental illness.

The mental health industrial complex is violent, perhaps most of all because it uses resources for survival to strip away our agency, and stops us from getting support when our lives are at stake.

If you’ve ever told someone you were thinking of suicide, you know how scary it is. Part of that fear lies in being emotionally vulnerable. Opening up about a stigmatized experience, or worrying about how your confidant will respond, can be terrifying enough on its own.

But for many of us, that fear extends further, to deep-seated worries that the cops will be called, our abusive parents will be notified, we’ll face hospitalization against our will, or our immigration status will be jeopardized. For queer and trans people of color, this second set of fears is often what stops us from asking for mental health support when we’re in crisis.

If it feels like I’m talking about you, I want you to thank you for staying alive. I see you, and I’m grateful you exist. Your fears are totally valid, and I’m sorry you’ve been hurt. I also want you to know that you deserve support, and I’m angry that you’ve been taught otherwise.

There are resources and strategies available to help you keep fighting for your life without compromising your agency or giving up your power. Here are just a few of them.

1) Create a Safety Plan

For most people, thoughts of suicide come when we run out of options. The more we’re oppressed, the less power we have, which means thoughts of ending our lives might come up a lot. To stay safe when suicidal thoughts are recurring, creating a safety plan can be a game-changer.

Safety plans help you recognize the early signs of mental health crisis, reminding you of steps to prevent self-harm and find support. They’re documents you create that are accessible, so you can grab them on short notice. They walk you through self-care options, provide contact info for support people in your life, and (if you choose) direct you to formal systems of care.

They’re based on the resources you want to use, and the ideas you deem helpful – so they’re a great way to ensure you stay in control during moments when you’re feeling powerless. There’s no “right” way to make a safety plan, but you can click here to access a generic template created by the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

2) Follow a Strict Self-Care Routine

Art by Zandra

When most people talk about self-care, their focus is on showing themselves love. When you’re feeling suicidal, chances are, this is the last thing you want to do.

A lot of the time, taking care of ourselves is the first thing to go when we’re in crisis, which cuts down our chances for healing. In these moments, it can help to think of self-care as a commitment, instead of a treat.

Remember your safety plan? Self-care strategies are a central element. Think about things that usually make you feel good – or even just sort of okay. Maybe this means taking a walk in the park or making art. If that’s too much, it’s fine to focus on basic survival stuff, like eating and sleeping every day.

Suicidal thoughts push back against your will to do some or all of these things. Do them anyways. Even if it sucks. Taking care of ourselves, especially when we’re feeling our worst, actually causes changes in our brain that help to lighten our mood. Therapists call this “behavioral activation.” It’s not easy, but it helps.

3) Learn the Rules of Mandated Reporting

As empowering as safety planning can be, sometimes it’s not enough. In those moments, a listening ear can be the difference between life and death. At the same time, there are a lot of really valid reasons why you may not feel able to talk to someone you know.

Suicidal thoughts are tricky to talk about, and that’s not just because the topic is stigmatized. Through mandated reporting, many of the support people we’d like to turn to in confidence have a legal obligation to disclose what we say in ways that could put us at risk.

Mandated reporting laws, which vary from state to state, are ostensibly created to keep us safe. For example, if a child tells his teacher he’s being abused, the teacher makes a CPS/DCFS report in order to get help. If a client tells her therapist she plans to kill her classmate, the therapist has a “duty to warn.” In a lot of situations, mandated reporting makes sense – but in cases of suicidal ideation, it often takes the form of 911 calls (which almost always means police interaction) or non-consensually notifying your parent or guardian, if you have one.

If you’re feeling suicidal, one of the best ways to take care of yourself is to find someone you can talk with openly. Mandated reporting laws are scary, but they don’t have to keep you from doing this. In most cases, a report is only required if you have a specific plan, and the means to carry it out. Even then, if you’re willing to take steps to ensure you’re not in immediate danger, you can minimize the risk that disclosures will be made against your will.

Before you tell someone you’re having suicidal thoughts, it can help to ask upfront questions about reporting. You can say, “I want to tell you about a hard time I’m having, but I’m not sure if you’ll keep it between us.” Or, “I want to give you some personal information, but can you remind me first about how you handle confidentiality?”

Mandated reporting is a state-legislated policy, which means that whether your doctor or math teacher wants to comply, they’ll likely be obligated. That said, the people in your life who know and love you most are probably not out to trick you.

At the end of the day, those you trust enough to talk with about suicidal thoughts are probably invested in your well-being. If you can be upfront with them about what’s on your mind, they’re likely to be open with you about the secrets they can and can’t keep.

4) Make a Check-In Plan

If you’re thinking about suicide, but don’t have an immediate plan to hurt yourself, you might want to consider setting up a daily check-in.

Take inventory of the people in your life who you trust enough to talk with openly. For this strategy, the people you choose can be peers, as well as mentors or support people. If you’re comfortable telling them you’ve been thinking of suicide, go for it – but you don’t have to. Call up your best friend, auntie, cousin, or coach, and explain, “I’ve been going through a hard time lately, and could really use your support. I wanted to know if we could plan some regular check-ins.”

Check-ins can be brief, informal, and done in the way that works for you.

You can try asking seven members of your support system to call you for a fifteen-minute chat, each on a different day of the week. You can plan to text back and forth with each of your besties between class. You can eat lunch with a different coworker every day at the same time.

Some people come up with code word they can use to let their friends know they’re in crisis. This can take the pressure off when you need more intense levels of support, but don’t know how to ask. The point is to keep you connected to the people who love and care about you, because the world is really good at making us feel alone, and that’s when we’re most at risk for suicide.

5) Access Anonymous Support

Getting support from people we trust can make a world of difference, but since many of us have been cut off from family and isolated within our communities, knowing about other options is vital.

Suicide hotlines, text services, and crisis chats and emails all offer alternatives to face-to-face support. They provide the chance to open up freely in moments where we don’t know who to call, or when concerns about privacy are too great.

If you use web chat, keep in mind that operators who feel you’re in immediate danger are legally allowed and totally capable of searching your IP address and having police sent to your door. That said, this is pretty uncommon. If you’re really worried, hotlines and text services are often harder to trace.

Check out the list at the end of this article for links to a few anonymous mental health crisis resources.

***

For many marginalized people, suicidal thoughts are just a part of life. The support systems within the mental health industrial complex are broken and scary for us to navigate, and you deserve much, much better. Please remember that staying alive is revolutionary work. I hope this information helps you keep agency over your body and your life and gives you the tools you need to keep going, even when it’s hard.

Resources

Crisis Text Line (chat with a crisis counsellor over the phone)

Laura’s Playground (support groups and suicide prevention chat for trans people)

LGBT National Help Center (crisis hotline and web chat for LGBTQ people)

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (crisis hotline and web chat for the general population)

Lifeline Crisis Chat (crisis web chat for the general population)

The Samaritans (anonymous email service for the general population)

The Trevor Project (crisis hotline, text, and web chat for LGBTQ youth under age 25)

Trans Lifeline (a by trans people, for trans people crisis hotline - no mandated reporting)

Youthline (crisis hotline, text, and chat service for LGBTQ2S youth in Ontario, Canada)

Love Is Respect (youth-focused crisis / resource hotline and chat focused on partner abuse)

RAINN (crisis / resource hotline and web chat for survivors of sexual violence)

National Runaway Safeline (crisis / resource hotline for runaway and homeless youth)

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

Image descriptions:

A person stands at a silver counter on the street. It appears to be a street cart in NYC. Their face is obscured by their curly hair, which is bright red with brown roots. There are blurred street lights and skyscrapers in the background.

A drawing of a face appears in the self-care section. The person has big brown eyes and long dark hair. But only the right side appears in color, whereas the left half of the face is in greyscale. Two-thirds of their lip is dark red, and the rest is a faded black.

About Lance Hicks:

Lance is a biracial trans organizer from Detroit, who has participated in and supported queer and trans youth organizing since high school. After navigating his own trauma and witnessing that of the youth in his chosen family, Lance enrolled in a clinical social work program in Fall of 2016. His vision is a world in which each of us has the tools and support we need to heal and to realize our own power.

About Eli Sleepless:

Eli Sleepless is a self-taught latinx film photographer. Their genderqueerness and nyc upbringing is important to their work. Find more of their work on tumblr, instagram, facebook, and our main page.

About Zandra:

Zandra is a trans woman of color and womanist extraordinaire who hopes to be a librarian someday. Her hobbies include researching random topics, writing, and reading.