"Yo El y Ella" by Diente

I have adapted to a new routine since Hurricane Maria made its way through Puerto Rico and Trump tightened the colonial grip on Boricuas on and off the island. My days begin and end with check-ins on Instagram and Facebook to find information on missing family and friends. I sort through messages from fellow Boricuas and curious friends. And then I cry.

I make sure to take pause to receive the love of my chosen family and make room for anger when others tell me to remain calm. When you understand the violent history of America’s military presence in Puerto Rico and the abuse of our people on and off the island, there is no reason to remain calm or expect help to arrive in the interest of the Puerto Rican people.

As of Wednesday, I am still waiting to hear from many family members. Today my cousin sent me a message that his wife is going into labor and waiting for a c-section. During my last conversation with my abuelo, he shared the news that he had just been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and was wetting the bed at night. He told me that he had lived a good life, and I promised to see him when I moved to Puerto Rico. I had put my life in storage to live at a queer feminist collective called La Rosario in Santurce. An unexpected surgery delayed my departure. I am writing this from the diaspora and grieving a Puerto Rico that only exists in my memory.

I am simply not ready to jump on the, “We will rebuild!” bandwagon when there are Boricuas without food and water being denied federal assistance because of illegitimate and predatory debt.

I am doing my best to prioritize self-care. I am redirecting anger into providing information on Puerto Rico’s colonial status; however, I cannot dissociate from the heartache. Each day the news simply gets worse and we are starting to process that the aftermath may be more deadly than the category 5 hurricane. No action can eliminate the exhaustion and the sorrow.

Contrary to posts on Facebook that say, “Puerto Ricans are Americans too,” I am reminding anyone who is willing to listen and some who choose not to that we continue to be treated as second class citizens and abused by our colonizer who is invested in keeping the island and its people isolated and poor.

Simply put, the framework of domestic violence mirrors colonial violence, and neither topic is openly discussed in America.

What many Americans fail to understand is that the Jones Act prevents foreign supply vessels from coming to Puerto Rico with much-needed supplies. Puerto Ricans already pay a high tax on goods that are imported. Food costs are already rising, and resources are becoming scarce. There is a 6:00 PM curfew. If the curfew is broken, an arrest is made. We are isolated on and off the island and at the mercy of a narcissist who would rather comment on the NFL than provide leadership.

Hurricane Maria has not only left our families in an extremely vulnerable position, but it is adding to the existing trauma of colonial violence inside and outside of our homes.

The neglect is criminal.

As Puerto Rico continues to suffer from flash flooding and structural damage, the diaspora is also being emotionally flooded. Our hearts are bleeding for Puerto Rico. I could spend a lifetime writing about the information I have received in the past week. The stress of bearing witness has also brought up feelings of helplessness. I can remember feeling helpless throughout my life when I could not afford a flight to attend a funeral or wedding in Puerto Rico or when the bank seized my abuela’s home. Prior to Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico was already at the mercy of a fiscal control board whose proposed solution to paying off debt including shutting down schools which are now acting as shelters.

When I feel like I am drowning, I give myself permission to come up for air, to seek refuge in Instagram and unplug to spend time in person with loves ones. I let myself cry when I shower and have access to clean water. I thank the Mother Earth for the food on my plate. I am embracing the changes to my routine. My day ends and begins with check-ins online and via text. When I feel survivor’s guilt, I think of my great grandmother Mama Julia who died in a plane crash on Good Friday on Pan Am Flight 526-A in 1952 trying to migrate to New York. I think of my ancestors from the mountains who healed themselves and their communities with tonics and basil leaves. I feel their presence with me when I wake up crying in the middle of the night thinking about my family that has received no rescue.

I am thinking with two brains: one is coping with trauma, and the other is coping with the fact that there are vultures waiting to profit from this disaster and Americans disappointed that their vacations have been canceled. I have begun speaking Spanglish to my friends as a way to cope with the enormity of balancing two languages and two worlds. It usually happens by accident. But if the world can consume the pop hit Despacito filmed in a area of Puerto Rico that has been destroyed, they should have no problem with our Spanglish.

Mostly importantly, I am coping with witnessing the effects of Hurricane Maria on all sides without losing a sense of self. Whether you are a Diasporican reading this or a global sibling affected by the violence of colonialism and climate change, I am with you. I love you. I see you. I hear your laughter and I am not afraid of your screams.

I do not pretend to understand what it is like to live in Puerto Rico at this moment without running water or electricity, but I do not understand what it is be Puerto Rican and experience all of the joy and pain that comes with it. I am not afraid to tell you that I am devastated, and I am not afraid to tell you that you need to act now to prevent unnecessary deaths.

Help Puerto Rico:

A List of Trusted Organizations Offering Aid

Disaporicans: Uniting the Disapora with Puerto Rico

10 Ways to Show Puerto Ricans Love

Donate Supplies Asked for by United for Puerto Rico

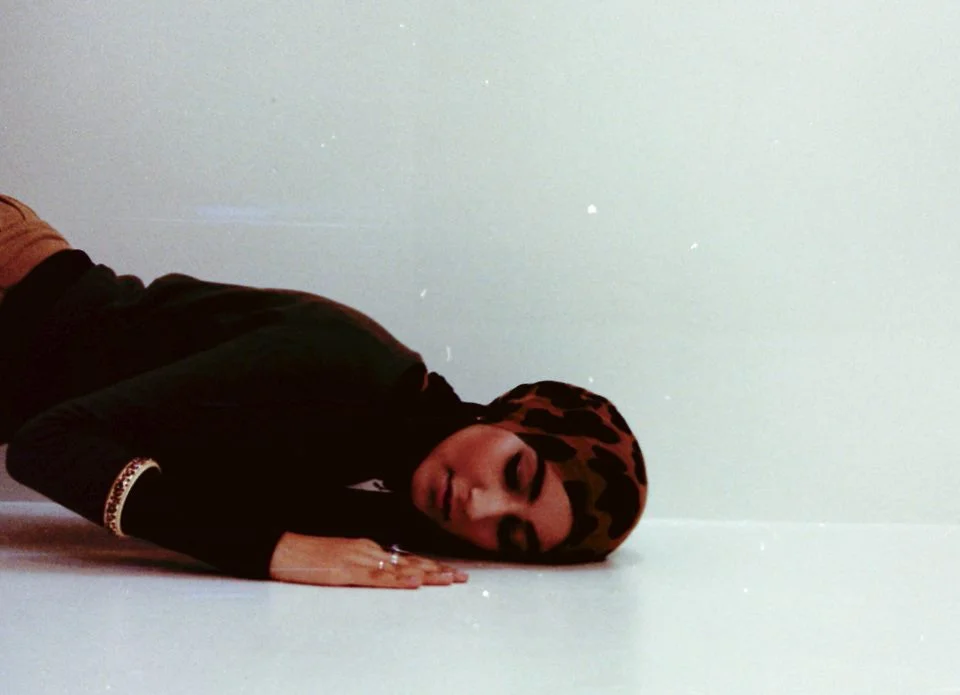

Image description:

Three faces are depicted, all with flowing long hair colored a mixture of white, grey, and brown. The central face looks ahead, and the two others turn towards the middle, shown in profile. They all have white eyes, thick eyelashes and brows, thick lips, and intricate gold face paint.

The title translates into "me him and her." This was created in the beginning of the artist's pregnancy. They were in the process of reconnecting with family and were feeling a lot of guilt and dysphoria around this time. The image captures for them how masculinity was fighting the maternal swelling. They would think: "I'm not papi, but i'm not mami either. I'm Mapi. I'm everything. Soy yo, el, y ella."

About Diente:

Diente, is a proud Cuir (Queer) Latine in Philadelphia, raised in a powerful Borinqueño household. Their art, a garden of decolonized flowers, sprouts from roots of plátanos y cafe to create edens for other children of the diaspora.

About Cassanda Lopez Fradera:

Cassandra Lopez Fradera is a journalist, storyteller and healing advocate. Raised in the northeastern U.S. and Puerto Rican diaspora, her work as a writer and public speaker is centered on providing resources and strategies for healing and self-determination. Through her reporting of local news on Café con Cass, she conducts interviews with civic leaders, multidisciplinary artists, mental health specialists, and change makers. Cassandra most recently worked in administration and as a union representative for HUCTW at Harvard University. In 2017, she received her Masters in Journalism Studies from the Harvard Extension School.

Lighting candles, burning sage, going to therapy, accessing medication, praying, giving offerings to the ancestors have all been ways that I heal at the intersections of my beautifully complex existence.